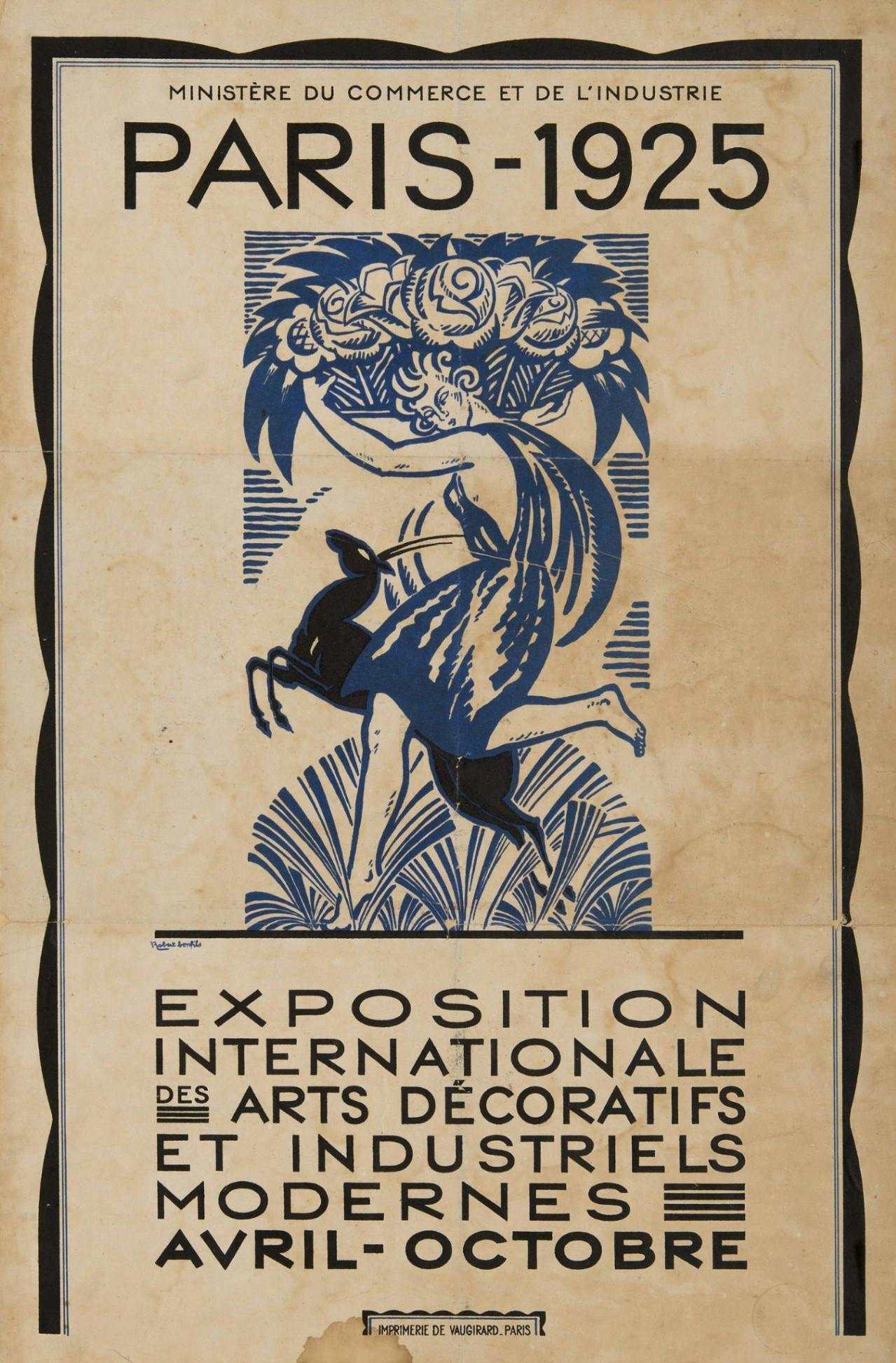

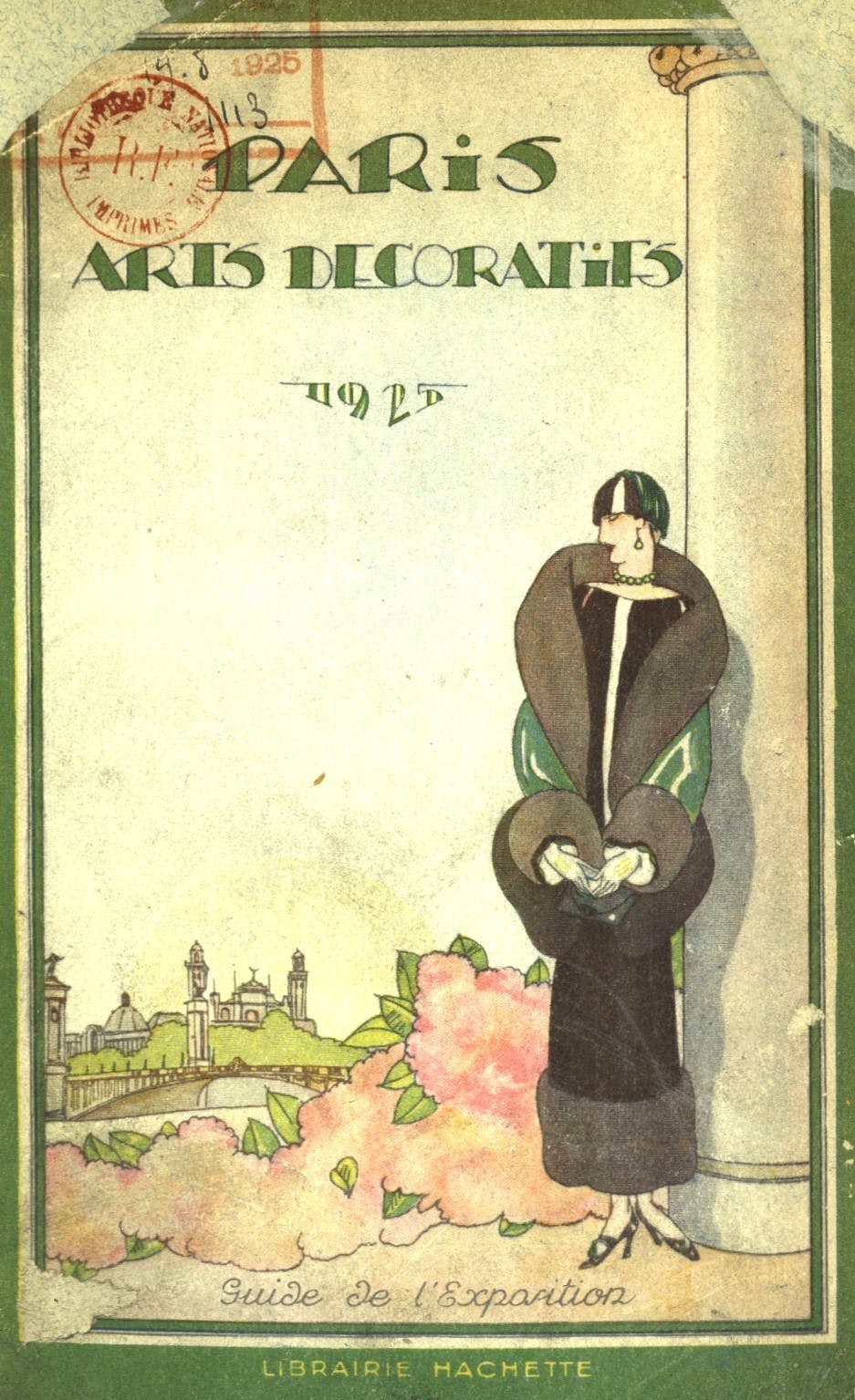

Leafing through the guide to the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes – the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts – is a very pleasant journey indeed, one that takes you through space and time. Inside, you discover an astonishing assortment of information: all the airlines operating in that day; advice on how to find a lost child in a train station; a list of Russian, Italian, and kosher restaurants; and even a brief guide to the catacombs. And then, at long last, starting on page 211, the third section gets to the point: “At the Exhibition.”

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&w=100&h=80)